HHPs in international governance

The cost of pesticides

A characteristic of all pesticides is that they were developed to inhibit the growth of organisms or to kill them. These characteristics have proven to harm not only the intended organisms, like specific pests, but also so-called non-target organisms like pollinators and humans. Their widespread use and open release in the environment has led to ubiquitous contamination of natural resources.

Those pesticides that are known to cause severe or irreversible harm to health or the environment under normal conditions of use, and are of high acute and chronic toxicity (e.g. carcinogenic, mutagenic or toxic for reproduction) are collectively called Highly Hazardous Pesticides (HHPs).

An estimated 44% of farmers suffer acute unintentional pesticide poisoning symptoms every year. In addition to the cost of purchasing a pesticide, there are many other ‘external’ costs that are often overlooked. These costs include inter alia:

- medical treatment and lost work resulting from pesticide poisoning

- loss of beneficial organisms including pollinators, fish, birds, soil microorganisms

- monitoring water quality

- disposing of obsolete stocks of pesticides

- recovery and disposal / recycling of empty pesticides containers

Unwanted pesticides often end up in loosely-secured stockpiles. According to FAO ‘Half a million tonnes of obsolete pesticides are scattered throughout [low income] countries. These toxic chemicals, often stored outdoors in leaking containers, are seeping into the soil and water, putting populations and environmental resources at high risk. In some countries they may be stolen from the stockpile and used indiscriminately on food crops.

Eliminating these dangerous stocks is expensive. To meet UN safety standards, the stocks must be re-packed, transported and (usually) shipped to a suitable high temperature facility. Currently, only Europe allows the import of pesticide waste for incineration. Discarded pesticide containers are a significant, global problem. They are much more hazardous than general plastic waste due to the pesticide residues they contain. They can lead to incidents of human poisoning and they contaminate soils and water.

The best way of tackling waste is to avoid generating it in the first place. Many countries, Ethiopia for example, have been the subject of repeated clean up operations. In the absence of measures to minimise waste, it has reaccumulated.

CropLife International boast that from the 40 mature container programs they support, farmers currently return 66% of all plastic containers shipped. Even in the fortunate locations with mature schemes in place, 34% containers are not recovered. The majority of locations have no such schemes, meaning that the containers end up being burned, buried, put into landfill. All these options lead to environmental contamination.

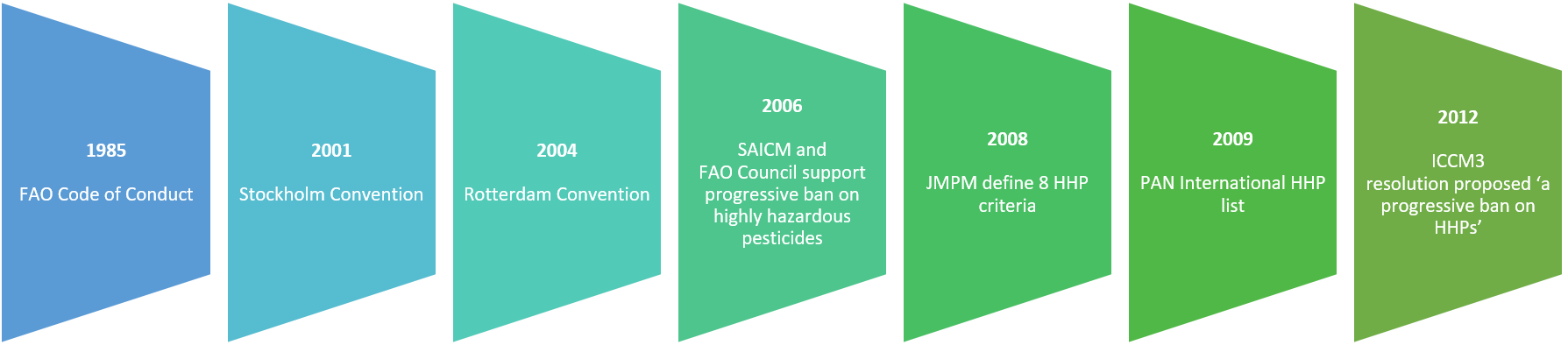

History of HHPs

The term Highly Hazardous Pesticides (HHPs) has only been in existence since 2006, but the HHPs themselves have existed for about 3,200 years, with the Chinese use of mercury and arsenic-based pesticides for controlling body lice.

HHPs in the ‘modern era’

It was the discovery of DDT’s insecticidal properties in 1939 that really ushered in the modern era of pesticide use. Mass production of DDT, and its introduction to agriculture began in earnest in the 1940s, quickly accompanied by other HHPs, including organophosphates, carbamates and phenoxy herbicides like 2,45-T and 2,4-D.

The start of the modern era of environmentalism is credited to Rachel Carson’s exposé of DDT in Silent Spring in 1963, but recognition of the adverse effects of DDT on human health began with the publication of a paper by a Drs Morton Biskind and Irving Bieber, US physicians, in 1949.

Global Governance

Since 1985, the number of regional and international legal instruments and conventions dealing with chemicals has increased by 80%, to approximately 50 agreements. But success in dealing with pesticide problems has been elusive.

The International Code of Conduct on Pesticide Management

In 1985, FAO’s governing body approved the first Code of Conduct: the FAO Code of Conduct on the Distribution and Use of Pesticides, now known as the International Code of Conduct on Pesticides Management. The Code was, and still is, voluntary.

Since the 1980’s the focus of efforts to reduce harms from pesticides in most countries around the globe has been:

- pesticide legislation on distribution, use and disposal

- pesticide registration to make sure that only properly tested and approved pesticides are sold

- training in so-called ‘safe’ and effective pesticide use.

Today, nearly all countries have put in place pesticide legislation. Many programmes aim to help low and middle income countries to properly register pesticides for distribution and use. And millions of farmers have been trained in ‘safe’ handling, use and disposal of pesticides by governmental organisations, aid agencies, the FAO, the pesticide industry and other private sector bodies, and by civil society organisations. But all these activities have failed to stop the pesticide poisonings. New figures show that 385 million farmers and farm workers suffer from unintentional pesticide poisoning each year. This is a predictable outcome in circumstances where regulation is weak, people are living under conditions of poverty and the use of PPE is neither affordable nor practical for the majority of end users.

Stockholm Convention

Next in line was the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (SC), adopted in 2001 and now ratified by 152 countries.

This Convention, although legally binding, has a profound effect on a small number of pesticides but a very limited impact on pesticides in general. All pesticides listed under the Convention are automatically regarded as HHPs as this listing is one of the criteria for an HHP.

Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent (PIC) Procedure for Certain Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade

The RC was adopted in 2004 and is currently ratified by 164 countries.

Unlike the Stockholm Convention, Rotterdam does not ban pesticides: it is simply a procedure to notify countries about particularly hazardous industrial chemicals, pesticides (active ingredients), and severely hazardous pesticide formulations. It says that chemicals / pesticides which have been banned, withdrawn or severely restricted in a defined number of countries should only be exported to a country if the importing country’s government has been informed of the reasons for the regulatory action and has given positive prior consent to the importation of the chemical or pesticide.

Only about 3.4 percent of all pesticides in use worldwide are covered by these two international conventions and thus globally restricted in trade or banned. By contrast, approximately 31% pesticides meet PAN’s criteria for HHPs.

SAICM and HHPs

In 2006, the Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM) was agreed at the first International Conference on Chemicals Management (ICCM1) in Dubai. As with the Code of Conduct, SAICM is not a legally binding treaty. However, it constitutes a global political commitment on the part of governments, chemical and pesticide manufacturers, civil society organisations and others. It is a broad global commitment which aims to foster sound management of chemicals, including pesticides.

Following intensive efforts to reduce the number of poisonings in developing countries, in 2006 the FAO Council recognised for the first time that certain pesticides could not be used without harm in developing countries, and responded to SAICM by recommending that:

“In view of the broad range of activities envisaged within SAICM, the Council suggested that the activities of FAO could include risk reduction, including the progressive ban on highly hazardous pesticides, promoting good agricultural practices, ensuring environmentally sound disposal of stock-piles of obsolete pesticides and capacity-building in establishing national and regional laboratories.”

![According to FAO ‘Half a million tonnes of obsolete pesticides are scattered throughout [low income] countries. According to FAO ‘Half a million tonnes of obsolete pesticides are scattered throughout [low income] countries.](https://www.pan-uk.org/site/wp-content/uploads/Obsolete-pesticides2.jpg)

According to FAO ‘Half a million tonnes of obsolete pesticides are scattered throughout [low income] countries.

To meet UN safety standards, the stocks must be re-packed, transported and (usually) shipped to a suitable high temperature facility.

As a result of this recommendation, in 2008 the FAO/WHO Joint Meeting on Pesticide Management (JMPM) developed criteria to define highly hazardous pesticides and recommended that FAO and WHO develop a list based on these criteria, to be updated periodically in conjunction with UNEP.

The criteria are:

- Pesticide formulations that meet the criteria of classes Ia or Ib of the WHO Recommended Classification of Pesticides by Hazard; or

- Pesticide active ingredients and their formulations that meet the criteria of carcinogenicity Categories 1A and 1B of the Globally Harmonized System on Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS); or

- Pesticide active ingredients and their formulations that meet the criteria of mutagenicity Categories 1A and 1B of the Globally Harmonized System on Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS); or

- Pesticide active ingredients and their formulations that meet the criteria of reproductive toxicity Categories 1A and 1B of the Globally Harmonized System on Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS); or

- Pesticide active ingredients listed by the Stockholm Convention in its Annexes A and B, and those meeting all the criteria in paragraph 1 of Annex D of the Convention; or

- Pesticide active ingredients and formulations listed by the Rotterdam Convention in its Annex III; or

- Pesticides listed under the Montreal Protocol; or

- Pesticide active ingredients and formulations that have shown a high incidence of severe or irreversible adverse effects on human health or the environment.

In September 2020, UNEP published An Assessment Report on Issues of Concern, and acknowledged that current instruments do not comprehensively address the sound management of HHPs at a global scale and that concerted international actions on HHPs are urgently needed and require for example, an international framework of sound management of Highly Hazardous Pesticides, possibly legally binding, and more engagement in alternative techniques that minimise chemical uses, such as agroecological techniques and integrated pest management.

Human rights and HHPs

Several UN Special Rapporteurs have made numerous references to human rights and HHPs. Most notable was the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to food, Hilal Elver, who in her report to the Human Rights Council in 2017 stated that:

- Reliance on hazardous pesticides is a short-term solution that undermines the rights to adequate food and health for present and future generations.

- To subject individuals of other nations to toxins known to cause major health damage or fatality is a clear human rights violation. [export of banned pesticides]

- Given the severe, negative impact of the use of hazardous pesticides on people and the planet, an international legally binding instrument to regulate, in international human rights law, the activities of transnational corporations would be important to strengthen the international accountability framework.

In his opening remarks at the 75th Session of the UN General Assembly 27 October 2020, United Nations Special Rapporteur on human rights and hazardous substances and wastes, Marcos A. Orellana made the following statements (extracts):

- “Regrettably, the, current practice of wealthy countries exporting highly hazardous pesticides and toxic industrial chemicals, which are banned on their home soil, to poorer nations lacking the capacity to control the risks, perpetuates global environmental injustice.

- States have a duty to “prevent and minimize” exposure to hazardous substances to protect against preventable diseases and disabilities.

An estimated 44% of farmers suffer acute unintentional pesticide poisoning symptoms every year.